Dear Young Conservationist,

It’s always a pleasure to write to someone who is interested in wildlife conservation. I think the best way I can help you at the outset of your career is to give a brief overview of the history of conservation, then say something about where it may be heading in the future, and finally try and give you some general pointers.

As perhaps you know, wildlife conservation has quite ancient roots but it emerged as a major field of human endeavour in the 1950s and 60s when it was recognised that a more global response was needed for the decline in wild species and their habitats (old growth forests, wetlands, coral reefs and so on). A little later the scientific discipline of conservation biology came together with the aim of informing the conservation community, and ultimately the wildlife authorities, about the state of nature and about the best policies and management options for more effective conservation. Another job for scientists was to diagnose the immediate causes of species declines and spearhead new techniques such as camera trapping (where cameras and motion sensors are positioned on trails) and environmental DNA surveys (extracting DNA of wildlife from hair, faecal material or the blood meals of leeches and biting flies) to find out where hidden or cryptic species occur. The main effort by the wildlife conservation community at that time, and still today, has been focussed on slowing the rate of wildlife decline.

It is perhaps worth adding that these days the term ‘wildlife conservation’ is often included in the more general expression ‘conservation of biodiversity’. Beyond that we have general environmental problems to consider – see my blog Advice for a Young Environmentalist.

So the overarching concern of conservationists today is to reduce the impoverishment in biodiversity that we humans are bringing about. The immediate causes of decline are well known and have not changed much through the years:

- Habitat loss and fragmentation;

- Species loss directly from overhunting and overharvesting;

- Arrival or introduction of alien species that predate on, parasitize, spread disease or compete with local species for vital resources, or which otherwise change the local ecology to the detriment of native species; and

- Ecosystem/habitat degradation from introduction of livestock, pollution or other human misuse.

To this list we can add a more recent arrival:

- climate change with its impacts on ocean currents, weather systems, polar icecaps and other terrestrial and marine ecosystems (it is still hard to predict how climate change will manifest itself and how it will interact with the other problems).

Two underlying drivers are responsible for all the above:

- Human population growth – this fuels demand for land and sea resources;

- The western economic system that aims for year-on-year economic growth. It has been widely adopted throughout the world, fuelling demand for more land and sea resources and for short-term (unsustainable) extraction of resources.

The way it works is that these two underlying drivers are now causing intensive exploitation of the Earth’s renewable natural resources – such as timber, non-timber forest products, fish and shellfish, game animals and their products (like ivory and rhino horn), fresh water (including aquifers that are recharged by rainwater), soils, etc. The exploitation of these resources is often at an unsustainable rate. To give just one example, much of China’s agriculture is based on underground water supplies which are being extracted at unsustainable rates. Consequently Chinese food production is predicted to decline by 37% in the second part of this century placing an enormous strain on the productive capacity of the rest of the world.

In tandem with overexploitation of renewable natural resources, we have increasing exploitation of the Earth’s finite natural resources – these are the fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal) and certain ancient underground aquifers. Burning fossil fuels is contributing massively to the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and hence to global warming and climate change.

There are some important issues which make the above conservation problems even harder to deal with:

- Different sectors of society have different ‘wildlife values’ and this causes conflict. For instance commercial users of renewable natural resources (like farmers and gamekeepers) naturally enough are interested in economic values and may attempt to exterminate wildlife which they see as pests or competitors; others who appreciate wildlife for its beauty or recreational value don’t like this (see my blogs Payment for Eden and Islands in the Gulf);

- An enormous gap between the richest and poorest in society which ferments conflict over who has access to, and rights to harvest or use, wildlife resources;

- Loss of local cultures which have used their local natural resources in traditional ways that are often more sensitive and more sustainable (but not all local cultures are perfect!);

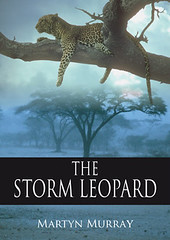

- A fundamental disconnection between people in modern society and nature. In fact this issue is like the ‘one ring that rules them all’ – it underpins all other problems. Ultimately the solution to the decline of wild nature can only come from a change in the human relationship with nature, which is what I talk about in The Storm Leopard.

So with this preamble in mind, how do we reduce conflict, improve conditions of the poor, protect other cultures and save biodiversity? These are deep and challenging questions!

Sea eagle off the Isle of Mull, Scotland

Photograph by Jacob Spinks flickr.com/photos/wildlife_boy1/with/9471687781

Recently a new narrative has begun to emerge in conservation – ‘rewilding’. Rewildling began life as a useful word to describe the reintroduction of animal and plant species to areas of their former rangeland. The release of white-tailed eagles on the Isle of Rum and European beavers in Knapdale are examples from Scotland. Some people are now using the term to describe the rehabilitation of entire ecosystems. Rehabilitation of the ancient ecosystem on Rum would mean a return to extensive woodlands (oak, holly, rowan, birch, hawthorn, aspen, Scot’s pine etc) supporting populations of wolves and bears. Rather than thinking about slowing the loss of biodiversity, rewildling is about recovering species and restoring intact ecosystems. It could revitalise economies and the ‘human spirit’ or, in less emotive terms, it could restore belief in ourselves and the motivation to create beneficial change in the environment. This idea has huge potential and I think it will grow in importance.

If I now try to answer your career questions in a more practical way, I would advise keeping a weather eye on the topics where the main funds for conservation are going. It’s a bit of a lottery trying to guess the future, but some of the hot topics emerging, or likely to emerge in the near future, are:

- Climate change and the carbon market (the discipline ‘environmental economics’ looks at ways of reducing CO2 emissions and many other topics relating to markets);

- Legal reforms in the environmental sector which are often a response to international environmental treaties (the discipline is ‘environmental law’);

- Building networks of protection across large landscapes and seascapes with corridors, islands, habitat restoration, etc. (‘landscape conservation’);

- Costing and budgeting ecosystem services (‘green economics’);

- Developing better mechanisms for monitoring natural resources and their exploitation (this kind of work seems to be developing in three directions: (a) remote sensing by satellite to monitor all kinds of changes; (b) use of DNA and other molecular techniques to determine which species are present in the sample of material obtained and even where the species originated from; (c) networking of information using website-mounted databases, and also projects that use ‘citizen science’ and ‘crowdsourcing’;

- Improving social mechanisms for solving natural resource conflicts and human-wildlife conflicts and other problems relating to governance of natural resources (taught in courses in the social sciences and in environmental economics);

- Designing efficiency into every aspect of modern life – buildings, transport, lifestyle, communications and commodities.

Similarly it is worth reflecting on the regions of the world and the ecosystem where we might expect major expansion of environmental work and conservation. They surely will include Antarctica and the southern oceans, the Arctic and Northwest Passage, China and East Asia, river catchments, coastal waters, and various arid regions in relation to water management. The plight of rainforests and coral reefs will continue to be critical because of the enormous variety of species.

I’m not sure that all these word pictures are going to help that much, when I imagine what you really want is practical advice about what to do next? The real decisions are in your hands but I can perhaps offer a few tips. Study hard to get a good grasp of the basic set of concepts and associated jargon that make up conservation biology. Keep aware of the big picture (sketched above) about wildlife conservation in relation to human demands on ecosystems. Most importantly, develop a specific skill or specialization on top of your general knowledge about conservation. It will become both your joy, and bread and butter. It could be the skill to negotiate over resource conflicts, or to a design wildlife corridor, or for revising the laws that protects the legal rights of indigenous peoples. Skill in economics will be needed for costing the ‘ecosystem services’ being supplied by forest ecosystems, mountain ecosystems and coastal ecosystems; other skills are needed for monitoring pollution in Arctic waters, or for designing energy efficiency into different kinds of building or enterprise. Any skill that you find interesting and challenging, and which can be applied to the environment and humanity, is surely worth developing – teaching, taking part in wildlife surveys, animal care (of orphaned animals or oiled birds for example), leading campaigns, artistic interpretation, and so on.

A completely different approach is to become an expert on one species, perhaps a symbolic animal like the peregrine, otter or basking shark in Scotland, or if looking abroad, like the large cats (lion numbers are in steep decline), elephant and rhinos (constantly under threat from poaching) or the stunning river dolphins (also under enormous threat from polluted and managed rivers), and then that species can become a tool for much wider conservation applications to save their habitat and related species.

To get this extra skill means seeking out training either when applying for university courses or when working for a conservation organisation, or just in your own time by taking opportunities that appeal when they come along. The important point is that you need conservation knowledge and something. This something will give you an edge over others and will open doors that are otherwise closed.

Universities – many offer conservation courses. You will need to do your own research as the situation is constantly evoloving. Here in Scotland, Stirling is becoming a centre for conservation. Aberdeen University is also good and has the new James Hutton Institute nearby but that has more of an environmental than conservation focus. Glasgow University Zoology Department is strong on animal diseases in relation to conservation and has major research projects in Africa, and the University of St Andrews is strong on marine ecology and conservation. In England, universities with good reputations for conservation are: Cambridge (largest single gathering of conservation groups anywhere in Europe, I imagine); Oxford (it benefits from David MacDonald’s ‘WildCRU’ which pioneers new techniques like camera-trapping). The University of Canterbury is also very strong with its Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology and it would be worth taking a look at the Universities of Lancaster and Exeter. I’m sure I’ve missed out lots of worthy candidates – so look closely at all of them and focus on what the departmental research staff are doing.

Whatever you choose, you will be engaged in one of the most worthwhile causes on the Planet; it may not bring you a great fortune in gold but it will reward you with a lifetime of brilliant memories and the fellowship of many excellent and committed friends.

Best of luck with your career,

Martyn