Earlier this month Charles Clover wrote (The Sunday Times, 3 October 2010) :

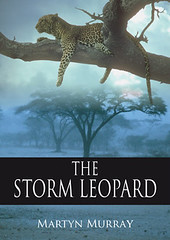

Martyn Murray, author of a new book, The Storm Leopard, is an ecologist who learnt his trade in Africa. He went back to assess the truth of the prediction made by an old Kenyan in the 1970s: “You mark my words, they will all disappear one day. Every single wild place.” What drives modern agriculture and modern development, says Murray, is the foraging strategy adopted by man in the Pleistocene era: killing more than we need to survive. This part of human nature sees biodiversity as a pest. Recently another force has emerged — the human imagination responding to nature, which can both heal the wilderness and make it pay.

A man rightly associated with that feat of imagination is Dave Varty, whose family game reserve, Londolozi, in the Sabi Sand, became a successful model for Africa… At Londolozi, two sculpted elephant tusks point in the direction of Varty’s latest vision, a wilderness corridor that lets wildlife flow from the Kruger national park to the Blyde River Canyon reserve and beyond, creating an economic opportunity for the rural poor, who now have better houses and schools but still need jobs. When you read Professor Sir John Lawton’s report Making Space for Nature, about ways of halting the decline of biodiversity in England, you wonder whether we have anything like South Africa’s vision, or ability to make it pay.

Will Africa listen to Varty’s vision for a Cape-to-Cairo corridor for wildlife, providing spiritual renewal, adventure holidays and rural development for an otherwise overdeveloped planet? Will we find a way of connecting our fragmented wildlife in this country and turning it to gold, whether on land or in the sea? The choice is between attrition and imagination. It’s up to us.

Britain has a much higher human population density than most African countries which is one reason why we tend to protect small sites (Sites of Special Scientific Interest) rather than large National Parks (I’m talking about the IUCN Category I or II protected areas which essentially have no permanent inhabitants, not the unusual National Parks of UK which often have human settlements). Nevertheless there is a reluctance to develop the network of protected areas, at least in Scotland, which appears to derive from something else. Here the large empty spaces with their deer, salmon, grouse, forests and moorland are owned by estates and there is a gulf between the common man and the estate owner. The Scottish Government is attempting to bridge that gulf but it is a slow process. Meanwhile there is a deal of mistrust and it is one of the brakes on our vision.

Pingback: The Storm Leopard | Your #1 Source for Kindle eBooks from the Amazon Kindle Store!